“Can you give me the 5-minute version of VTS?”

WRITTEN BY DABNEY HAILEY

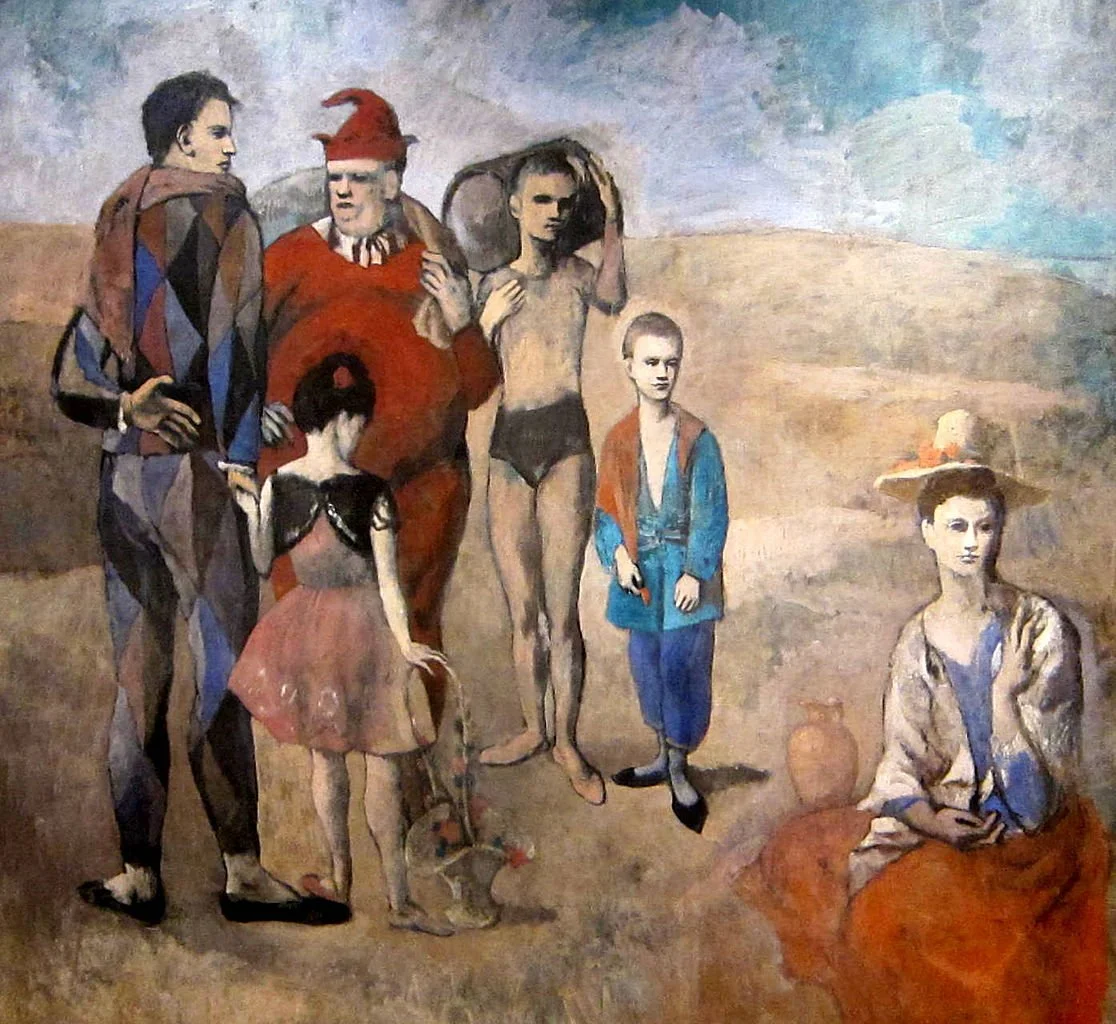

Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, 1905, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

“That was great! Can you give me the 5-minute version?” a participant in one of my first business-focused workshops asked.

His excited question followed an intensive, 30-minute group discussion I had just facilitated about the painting reproduced here. We were reflecting on how the structure of our discussion—I was using the methodology, Visual Thinking Strategies—enabled multiple perspectives to arise, allowed us to test ideas in evidence, and kept us looking and thinking deeply before jumping to premature conclusions.

The questioner, who appreciated the discussion, instinctively wanted to accomplish the same depth of inquiry in much less time, and who could blame him? Most contemporary workplaces have a strong bias toward action, and “action” is often code for solving and deciding. But thinking rigorously together is itself a valid form of action.

Before answering, I paused briefly to give everyone a bit of space to consider his query. Even before I could finish my gentle reply, “Well, what might a 5-minute version look and feel like?” the questioner and his colleagues were chuckling.

“Wait, I guess there is no 5-minute version,” he said with a sheepish smile. Thirty minutes of a team’s deep inquiry and exploration cannot be packed into five when the subject of discussion is something as ambiguous and layered in potential meanings and outcomes as a great work of art—or a business strategy, product in development, user experience analysis, marketplace, complex data set, or a financial statement—really any ambiguous problem or project. Five minutes means only a couple of voices are heard and most details are missed. Those voices are often the loudest, which means many never add their own expertise and varying ways of making meaning. Missing details means potentially making mistakes and wasting time later.

The 37 workshop participants were all SVPs and VPs at a major financial services firm. They were at the beginning of a three-month intensive leadership training, a series of projects and experiences designed to shift them from focusing on execution to focusing on thinking and strategy, and to build their facilitative leadership skills.

As we continued to reflect on the VTS discussion that day, we considered the depth and reach of the 30 minutes we’d spent looking at the painting—what had actually come up? We’d noticed the range of figures and how their gazes, gestures, clothing, and expressions could be variously, often paradoxically, interpreted. We had postulated a range of ideas about who was communicating with whom (or not), what kinds of relationships the figures might have to one other, and how gesture, gaze, color and placement were inflecting our answers. As we delved into various details (a mysterious vase, a swab of brown, a pair of feet set in a dance position) and then back out to generate narratives about the picture as a whole, we were also scaffolding each other’s ideas, building interpretations, and letting go of ideas unsupported by visual evidence.

Significantly, it took more than twelve minutes for anyone to mention the setting of the scene—the landscape behind the figures. It looks somewhat empty and lacks particulars, being mostly sky and bare ground with what may be a road or path. Once someone voiced an observation about the setting and pulled its details and palette into the ongoing analysis, certain narratives suddenly took on new life. Several people decided the figures must be on their way from one place to another, pausing in limbo and indecision; others thought they must be outside a town, waiting to perform; still others began to imagine that two of the figures were not really there at all but figments of another character’s imagination or memory. Exploring the background in relationship to the figures took the conversation to new levels and greatly expanded our interpretations. To get to this level of complexity, we needed ample time and many voices. We needed to resist snap judgments, “right” answers, and the compulsion to stop looking—my facilitation of the discussion held us in rich, wondrous inquiry as we kept observing, listening, learning, and sensemaking. (In other posts, I’ll dig more into the lenses and diversity of thinking we regularly generate through VTS and how it connects with frameworks like Kahneman’s “fast” and “slow” systems.)

For the remainder of that day’s workshop, the executives broke into small groups and were coached as they took turns facilitating open-ended, carefully structured conversations about works of art using VTS techniques. They began to revel in the openness yet rigor of the methodology and appreciate each other’s perspectives, even in disagreement. They also learned to allow time and space to find the equivalent of Picasso’s landscape in the first discussion—that crucial setting that subtly shifts our understanding of the whole picture and each other—as we looked at their own business materials.

Can you imagine solving a complex business problem or establishing a strategy without considering how something like context is impacting your reasoning and decision-making? Is it possible to determine the various layers of possibility, potential pitfalls, and applicability of a new project or product in only 5 minutes, or what amounts to a cursory glance? Or even through typical meeting structures, like quickly going around a room for input without any deeper questioning, thoughtful listening, or encouragement for new lenses? What kind of results might you see if you create periods of exploration and inquiry into your decision-making processes, rather than leaping to judgment and moving on?

As for that first questioner, whose compulsion to want a fast, “right” answer in very little time was felt by many in the room, a few months later, he shared his gratitude. Trying to lead a VTS discussion shifted his perception of his listening (“I don’t think I ever actually really listened before this!”) and his ways of showing up in the world. His insights were profound and registered across his life, from family to work relationships.

When we slow down and listen to one another, we’ll later arrive at far more robust right answers and develop a more positive team culture to boot.